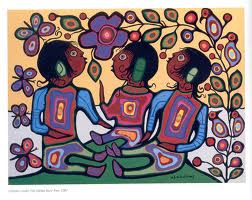

Can you imagine a life where everyone is equal and that no one person is greater nor less than? This was the way of our people prior to European contact. There were many nations or communities all over what is now called Canada. Everyone had a role within the family and within this system was a equal and balanced understanding. According to the manual Reclaiming Connections;

Understanding Residential School Trauma Among Aboriginal People, "Holism means awareness of and sensitivity to the interconnectedness of all things: of people and nature; of people, their kin and communities; and within each person, the interconnectedness of body, mind, heart and spirit" (Chansonneuve, 2005 p.23).

Before the contact of non Aboriginal peoples, "the Anishnabe peoples operated on the basis of community welfare; the value placed on the best interests of the community or group was more crucial than the interests of the individual. Survival of the group was the primary concern. All members shared equitable shares of any goods that were provided" (Turner & Turner, 2009, pg.97). This was with respect to the relationship of all animals, all community members, and all the land (Mother Earth or Turtle Island). There was no such thing as ownership, the people took what they needed and gave thanks by returning offerings such as; semaa, sweat grass, or by ceremonies.

The Aboriginal peoples were healthy and lived off the land through hunting fishing and trapping. They did not waste anything nor did they take more than they needed. Everyone shared within the community and there was a mutual respect for all, from the youngest person to the oldest. The overall health of the community depended on some of the medicines that were made by the Traditional healers in the community, "Traditional healers used the roots of trees and plants to produce drugs such as

quinine and

ipecac, a potent medicine that cured otherwise lethal intestinal infections (Chansonneuve, 2005, p.23).

Although, after European contact, from my understanding a lot of the research came from autopsies or studies retrieved from Aboriginal remains that were dug up from burial sites and or found and sold to buyers. Researchers, scientist or authority figures where infatuated to know everything about the Aboriginal peoples of this land. When they starting to collect and study these remains they would document and retreat everything found with the remains such as all bones, sacred items, clothing, and hunting gear.

Even though there are many unanswered questions, "The Study of human remains from various regions in Canada provides substantial evidence for disease and nutritional compromise of varying degrees and kinds, prior to European contact. Fungal, bacterial, and parasites infections afflicted pre-contact peoples to varying degrees, depend on socio-ecological conditions"(Waldram, Herring & Young,

2006, pg.46). These results had a lot to do with issues surrounding overcrowded living space, certain animal foods they ate, and insects.

In toady's society, "Many of the statistics about disease and illness among Aboriginal people have been published and are well known. Illnesses resulting from poverty, overcrowding, and poor housing have led to chronic and acute respiratory diseases" (Frideres & Gadacz, 2008,

p.79). As we work in the communities today we still see a huge need for proper health care services. Canada has come a long ways in the 20th century but still there are more disease and health concerns for the Aboriginal peoples than ever before.

Although, there are many different perspectives to current issues of the health and well being of the Aboriginal peoples today, we need to examine why this is? How in a land so rich and filled with resources and minerals, there is so much disparity, inhuman treatment, and that the living conditions resemble third world countries? In order to fully understand why there is so much issues concerning this group we must understand history, the true history.

It is understood that through the colonization process, it can be placed into seven parts; the first attribute is the Aboriginal peoples lands and resources were taken away and they were placed on reservations; the second attribute was that the European colonizers destroyed the Natives peoples' political, economical, kinship, and in most cases religion- also this is when Indian Act 1876 where Indian lands for sale- strategies to civilize and Christianize them- residential schools- kill the Indian in the child- also passed legislation to outlaw dances and ceremonies; the third and fourth attributed aspects of colonization are the interrelated processes of external political control and aboriginal economic dependence; the fifth attribute of colonization is the provision of low quality social services in such areas of health and education; the sixth and seventh attributed aspects of colonization relate to social interactions between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginals people and we can refer to racism and the establishment of color-line (Gadacz & Frideres, 2008).

Through out history, direct tactics to colonize, assimilate, and destroy the Aboriginal peoples and with great impacts of intergenerational trauma, lateral violence, shame, loss of culture and identity, lost of language have direct negative affects. This is why we see high stats to destructive behaviour in the court system, high rates of suicide, mental health problems, child poverty, over whelming children in care, substance abuse, violence in the home. We cannot assume anything as each individual, person in environment, are different from the next, but we know that past historical events must be present when issues that concern the health and well being of any individual.

Migzs...Tammy......

References

Chansonneuve, D. (2005).

Reclaiming connections: understanding residential school trauma among aboriginal people. Aboriginal Healing Foundation. Ottawa, ON

Frideres, J, S., & Gadacz, R, R. (2008).

Aboriginal peoples in canada (8th ed). Toronto, ON: Pearson Education

Turner, C. & Turner, J. (2009). Canadian social welfare (6th ed). Toronto, ON: Pearson Education

Waldram, J, B., Herring, D., & Young, T. K. (2006).

Aboriginal health in canada: historical, cultural, and epidemiological perspectives (2nd ed). University of Toronto Press (BPIDP).